Needles, California: A railroading oasis

If you’re a fan of the Peanuts cartoon by Charles Schulz, you might remember Snoopy’s brother, Spike, who lived in Needles, California. Spike is said to have lived by himself with only a cactus for company, but Needles is an oasis for railroaders and railfans alike in the middle of the Mojave Desert.

Named for the sharp peaks at the southern end of the Sacramento Mountain Range, Needles was founded as a crew change point for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (A&P), a forerunner to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (ATSF or Santa Fe), one of BNSF’s major predecessors.

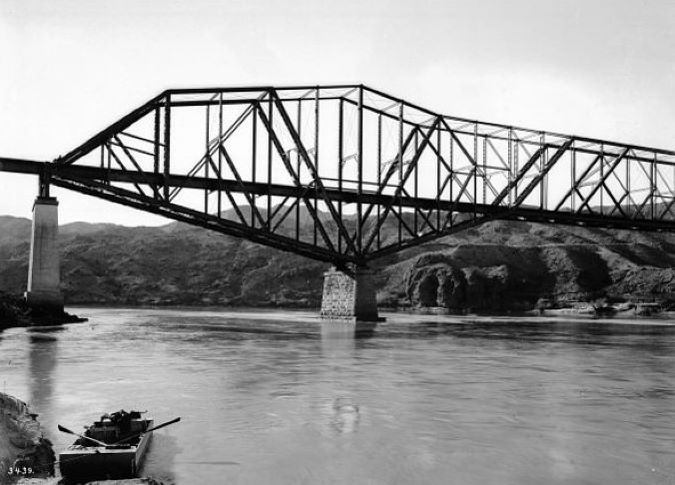

Located in the heart of the Colorado River region, Needles is across the river from Arizona and a short drive from Nevada. In 1883, the A&P expanded west across the Colorado River from Arizona to create a transcontinental railroad, though this was not the first of its kind.

From the very beginning, Needles has been tied to the rail industry. Retired BNSF locomotive engineer and volunteer at Needles Regional Museum Keith Jones said the town was primarily populated by the Santa Fe as it recruited workers.

“This town exists because of the railroad. At one point, the Santa Fe built houses in Needles for officials and their families to live in,” Jones explained. “It was to create housing that didn’t exist.”

The Santa Fe even built a recreation hall for Needles-based crews with a reading room, a state-of-the-art gym and an indoor swimming pool, where many of the local children learned to swim. From billiards to an auditorium, to a three-lane bowling alley, the hall had it all. The main building had two additional wings with extra rooms that could be rented by ATSF employees. Years later, the building became Needles’ city hall and burned down in 1976.

“The rec hall isn’t here anymore, but the baseball field next to the old stockyards is. Before cell phones, train crews, myself included, would watch baseball while we’d wait for our call,” Jones said.

Finding entertainment for these railroaders was a small issue compared with the extreme heat of Mojave Desert summers. Needles often reaches temperatures near 120 degrees, and before air conditioning, crews created unique ways to beat the heat. “Cooling sheds” were small structures with tin roofs and canvas flaps around the sides. The tin roof was equipped with a sprinkler-like device that drenched the canvas with water. When a breeze came along, the air inside was cooled from the water-soaked canvas.

Being a town along a transcontinental network, a little bit of everything was, and still is, moved through Needles.

“Well over 100 trains come through Needles some days – sometimes 125,” Jones said. “All kinds of freight moves through Needles because it’s part of BNSF’s southern transcontinental route from Los Angeles to Chicago.”

Some of the freight being shipped east was produce from California’s farms and orchards. Needles was essential for this freight because the town had an icehouse needed for cars containing fruits and vegetables to prevent spoilage.

Some freight being shipped west included livestock. Needles was a stopping point for livestock too as the animals needed a place to rest, eat and get water. The livestock would be reloaded and continue their journey into California.

The Needles yard provided relief for train crews and steam engines, which would stop here for water to help fuel the last stretch of their trip west.

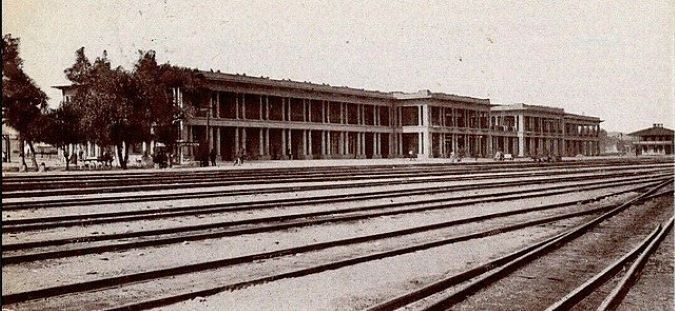

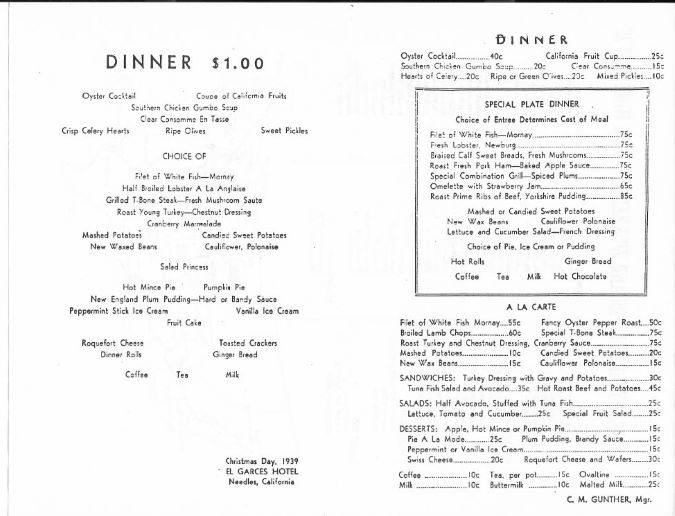

Like many railroad towns in the Southwest, Needles was home to a Harvey House: the El Garces Hotel. The Harvey House, a chain of restaurants and hotels alongside Santa Fe tracks, was owned by the Fred Harvey company, which was dedicated to hospitality for rail travelers. These trackside hotels benefitted both companies by attracting tourists and celebrities while creating a new standard in rail travel.

El Garces was built in 1908 next to the Needles train station as a hotel and dining room. It was designed by architect Francis W. Wilson and cost $250,000 to build, equivalent to $8.2 million today. The hotel had 60 guestrooms, a lunchroom seating 73 and a dining room for 140. It was considered the “crown jewel” of Harvey Houses.

Michael Thornton, former BNSF locomotive engineer and current volunteer and tour guide at El Garces, said that the hotel isn’t just important to Needles, it’s the centerpiece of an old frontier town.

“The El Garces had a huge impact on Needles because it brought in so many people,” Thornton explained. “Back in the day, writers said it was difficult to move in the lobby because so many people were there.”

Many celebrities, including Harry Houdini and Charlie Chaplin, stayed at the El Garces. The chain’s high standard was maintained by waitresses known as “Harvey Girls.”

The onset of World War II made it difficult for the Harvey standard to continue. The Fred Harvey Company recruited many of its chefs from Europe and with war across the world, this quickly became complicated.

The war didn’t just impact chef recruitment; the Harvey Girls couldn’t continue serving in the iconic Harvey fashion as they were now serving soldiers as part of the war effort. According to Thornton, Harvey Girls served around 1 million meals to soldiers every week. All Harvey Houses closed by the 1950s, including El Garces, which closed in 1949. Santa Fe tried to operate El Garces as a hotel for a short time, but ultimately it closed again.

Today, El Garces serves the city of Needles as a popular event venue for meetings, celebrations and reunions. A few of the hotel’s historic rooms have been restored and are available to rent in addition to the newly founded guided tour program.

Needles still has an authentic railroad town feel, and BNSF plays an influential role here, with over 400 employees in the area. Locomotive engineers and conductors, plus a team of Engineering and Mechanical employees, work together to keep this important line operating safely and efficiently.

Tim Coleman, superintendent Safety & Operating Practices for the California Division, has a longstanding relationship with Needles as he was a locomotive engineer in the area for years.

“Needles, since day one of its inception in 1883, has been an integral part of the railroad industry, particularly on the West Coast,” Coleman said. “Needles grew in prevalence as it gave access to Barstow and San Bernardino (California) in the early 1900s. Today, it’s still a hugely instrumental intermediate location.”

Staying true to its transcontinental railroad roots, many kinds of freight are still moved through Needles, especially intermodal traffic.

“We see intermodal trains with consumer goods of every kind imaginable, plus manifest trains with a wide variety of cargo, as well as grain and work trains,” Coleman said. “Basically, anything we need as a nation, BNSF is able to provide economical shipping options – and Needles plays a big role in that process on our Southern Transcon.”

Lena Kent, general director Public Affairs for California, sees firsthand how important Needles is to keeping freight on the move.

“BNSF is proud of its rich heritage in Needles, which played a key role in developing the West and Southern California,” Kent said. “Needles continues to be an integral part of our Southern Transcon, supporting the safe and efficient movement of goods between California and the rest of the nation.”

Did you know?

The Needles Mechanical team has not had a single injury in 31 years.

Since 1992, this team, currently nine members strong, has successfully performed their job functions without a single injury. The impressive dedication to perfection in safety for over three decades amidst extreme desert weather and heavy equipment is something to be proud of.

Through their commitment to safety procedures, communication and teamwork, the Needles crew has demonstrated that mechanical job tasks can be navigated injury-free when the right mindset and practices are in place.

“We can attribute this streak to our continued on-the-job training and focus on our task at hand,” said Jeremy Hutchinson, mechanical foreman, Needles. “We’re working out on the road where we change wheels and repair railcars and locomotives so we’re constantly working around moving equipment, active tracks and other potential exposures. Every day, we have to really hunker down and focus and communicate with each other.”