Freight wonders of the world: How BNSF solved five big engineering challenges

Without a railroad, fledgling towns in the developing West didn’t stand a chance. But how to get the tracks and eventually trains bringing people and freight through a remote and sometimes unforgiving land challenged some of the most astute engineers of the day.

Snow-covered mountains in the Northwest and steep canyons and gorges in the Southwest were just some of the obstacles engineers and their crews faced. Thanks to their ingenuity, perseverance, manpower and machines, the railroads arrived. Towns that might have faded away prospered, many becoming bustling cities.

Fast forward more than a century. That growth – plus demand for faster, safer and more freight rail service – creates new engineering dilemmas. Highways and downtowns have to be circumvented, with track going under or over congestion. A single main line may not be enough to handle today’s train traffic, so double or triple track is added, in places where the terrain is not always accommodating.

These and other challenges keep BNSF’s Engineering Department at the drawing board, creating new marvels that may eventually join the history books. Here’s a look at five of BNSF’s most notable engineering wonders dating to the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

Marias Pass

In the race to get a transcontinental railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean – a 2,000-mile route over arid plains and two great mountain ranges – BNSF predecessor Great Northern Railway (GN) faced many obstacles, including the Rocky Mountains.

GN Chief Engineer John Stevens and a guide found the best way to cross, through Marias Pass in northwestern Montana. On Dec. 11, 1889, in 40-below-zero weather, Stevens found the long-elusive pass, offering a superlative low-level route over the Rockies at only 5,213 feet above sea level. Located in the southern boundary of today’s Glacier National Park, the pass avoided a 500-mile detour and offered a gentle grade that would not require extensive excavation.

Construction on the line traversing the pass began in 1890. The final spike was driven near Scenic, Wash., on Jan. 6, 1893, completing the transcontinental project. By midsummer of 1893, Seattle and the East were linked by regular service. Today, this segment is part of BNSF’s Hi-Line and those who travel the line on Amtrak can see a bronze statue of Stevens on a ledge overlooking the pass.

Stevens Pass and Cascade Tunnel

When a mountain range gets in the way of a railroad, there are a few options. You might get lucky, like Stevens did when he found Marias Pass. You can go around the range, but that takes a lot longer. You can go over it, through a series of switchback tracks that zigzag up the mountainside. Or you can go through it with a tunnel.

When it came to Stevens Pass, named for its engineer, GN first overcame the steep grades of the Cascade Mountains in western Washington using a series of switchbacks. Extra locomotives in the lead as well as the rear were required to lug trains up the mountain.

In 1900, a 2.63-mile tunnel replaced the switchbacks. But the tunnel was plagued by snow slides, including the deadliest avalanche in U.S. history. That disaster prompted a change. In 1929, GN created a new line 1.5 miles south and 500 feet lower than the original line, eliminating the winding route and avoiding the snow zone. The new main line track included the then-longest tunnel in the Western Hemisphere, the 7.9-mile-long Cascade Tunnel.

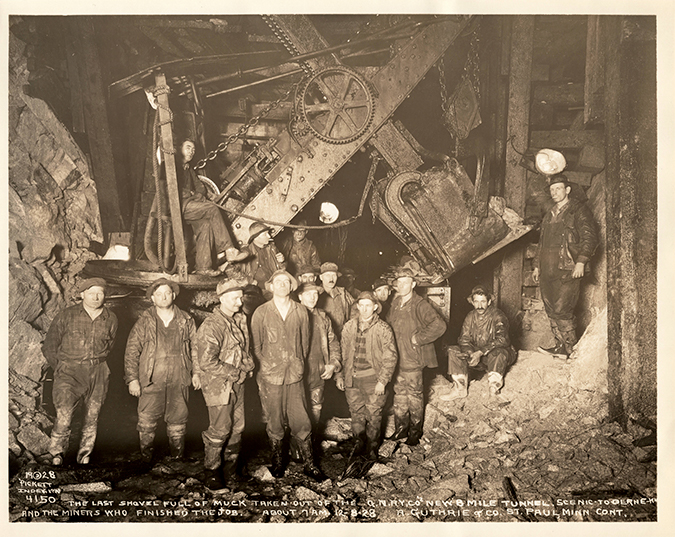

Construction on the tunnel began in December 1925, with a temporary “Pioneer Tunnel” built at the site for construction purposes. Some three years later, with nearly 1,800 men working on the project day and night, moving 934,600 cubic yards of rock and earth and placing 262,562 cubic yards of concrete, the tunnel was dedicated Jan. 12, 1929. Several million Americans listened on their home radios as President-elect Herbert Hoover and other dignitaries dedicated the opening.

Canyon Diablo Bridge

In the 1880s, engineer Lewis Kingman faced the challenge of building a bridge east of Flagstaff, Ariz., where the conditions are harsh and dry and the location desolate. His railroad, predecessor Atlantic and Pacific (A&P), needed to connect to the West Coast, and in the way of that plan was a chasm – Canyon Diablo, or Devil’s Canyon – more than 225 feet deep with steep sides and 500 feet across at the top.

Bridge builders were sent to the site months before the rails arrived, with crews hauling supplies as the railroad approached the site from Winslow, Ariz. The bridge iron – 20 carloads worth – was prefabricated in New York and designed to hold 30 times the weight of the trains it would carry. Limestone pillars for the bases were excavated from nearby deposits and chiseled by stonemasons.

Once assembled, the trestle bridge stood 220 feet above the canyon floor and stretched for 544 feet from one side to the other. The first trains passed over the canyon on July 1, 1882.

A sturdier bridge replaced the original in 1900 at the same spot, and then in 1947 the double-track, steel-arch bridge seen today was completed. Its length is 544 feet and its arch measures 300 feet. While remote, this is a popular site for railfans to photograph BNSF trains.

Abo Canyon

Part of our crucial “Southern Transcon” route connecting Los Angeles and Chicago, Abo Canyon near Belen, N.M., was one of the last major pieces of single track on this important line. Adding a second track posed physical challenges as well as preservation concerns when construction began in 2008.

Built in the early 1900s, the existing 5-mile single track wove around 400- to 500-foot-high bluffs, through cuts 100-150 feet deep and over 70-foot high bridges. Adding a line was complex given the canyon’s shape and limited access – but the second track was needed to relieve this pinch-point.

Excavation would be significant; ultimately 3.6 million tons of rock had to be blasted. But before any work could begin, there were environmental issues to work through to obtain permits, investigations of local endangered species as well as an extensive study of archaeological resources.

Within the canyon is rock art dating from 1400 A.D., so BNSF designed the project to minimize the impact on these and other cultural sites. Bighorn sheep that had been reinstated in the canyon needed protecting as well, so a wildlife fence and crossings through bridge openings were engineered.

Among other engineering requirements was that there be reduced curvature of the new line to allow for increased train speeds. The new alignment also reduced rock fall hazards on the existing track as well as provided another track for trains to run on during maintenance. Nine new bridges had to be constructed to mirror the opening and waterway capacity of the 100-year-old bridges on the original construction.

Nearly three years later and ahead of schedule, on June 3, 2011, the first train traversed the completed double track.

Argentine Flyover

Kansas City is a busy rail hub, second only to Chicago, and also part of our Southern Transcon.

Given the number of railroads and trains that operate here, the KC Terminal Railway was formed as part of a public-private partnership by railroads operating in the area to coordinate the use of tracks and to finance the Argentine Connection Flyover – essentially an overpass. The Sheffield Junction, another flyover just a few miles east, was similarly built in 2000.

Work on the two-mile Argentine Flyover began in 2002, running east-west and connecting the Kansas City, Mo., Union Station with BNSF’s Argentine Yard in Kansas City, Kan.

The $60 million Argentine Flyover opened in September 2004, creating three levels of track that enabled increased train speeds and reduced congestion.

Today, BNSF’s Engineering team, like our predecessors, is committed to providing a safe and reliable track and infrastructure to keep our trains – and customers’ goods – moving.

“The most successful engineers in our industry’s history have been able to build projects that reflect the business need at the time and that can also be further enhanced and improved over the course of time,” said Craig Rasmussen, BNSF’s assistant vice president, Engineering Services & Structures. “Today, the same principles are largely still in play. Engineers know the most important elements of decision making are to ensure safety is held paramount, while building infrastructure that can be efficiently operated and maintained for generations to come.”